This entry consists of two parts. The first will examine the digital realm as sublime in its existent format, discussing issues of tangibility and ownership. The second will discuss how digital technology can portray sublime concepts in ways not possible within analogue mediums.

To recall Schopenhauer’s previously mentioned analysis, he stated that the highest feeling of the sublime is the contemplation of the scale and longitude of the universe.

The digital realm runs alongside our own existing one, through human made devices, but with limitless freedom and space, its own invisible universe, with parallels to draw with our own reality.

The strongest link is the concept of scale. Neither our universe, nor the digital counterpart, has an outer limit. There is a constant expansion occurring into nothingness, making both impossible to map or to put into perspective. The digital world is neither a container nor an object, and so it can never be filled with data, which serve as the replacement for physical objects in this universe based metaphor. Rather than being added to a form, there is a spread outwards, unconfined as the space has no boundaries. Servers to host web space can be brought and set up, as can new storage devices. The only limitation is the demand of the users; if there is no need for extra space, the demand for the products will stop and the devices will subsequently stop being manufactured. Trying to draw a sense of scale from this immeasurable expanse pushes the imagination to its limits, relating back to Kant’s theory on the sublime as a psychological state where the mind fails to process the information it is presented with.

To address Schopenhauer’s assessment again, duration can factor once again in both worlds. NASA has estimated that the age of the universe is “around 13 billion, give or take a few billion.” (NASA, 2011) The first computer, ENIAC, came to fruition in 1946, 65 years ago, a miniscule amount of time, which may make the comparison of duration sound completely absurd. However the issue is not the amount of time, but the progression of technology within those sixty years, and where it will be in another sixty. The rate of evolution is what gives such a comparison more gravitas; within the said time machines have moved from basic mathematics to displaying interactive virtual environments. The technological revolution is well documented and on-going, however it is the impossibility of prediction what it will lead to in a larger amount of time, for instance 1000 years (still a tiny amount of time when compared to the universe) that engages the mind in implausible speculation that is similar in feeling to that when contemplating the estimated 13 billion years of the universe.

This rate of progression also reveals the fleeting nature of the files with which we fill our digital worlds. As technology updates, so do the formats in which files are stored, as the language from which files are read evolves, and previous forms become inert unless translated and updated, much like human language. Eventually files are left as symbolic strings of binary, the final base language of computing. Even the devices that these are stored on, DVDs, USB pens etc., will become obsolete and unreadable, in the same way floppy discs are no longer in use with personal computers. Photographs, films, personal documents, without a physical copy such as a photo album or film reel, will become lost in the seas of endlessly generating data. In this aspect, data can be serving as a metaphor for human existence; consider how difficult it is to trace a family tree past a few generations. This momentary existence ties into the duration of the earth, and how it will continue for billions of years again, once this moment has passed.

Digital files very existence can be called into question however, removing them from a comparison to humanity. If a file is intangible, it is difficult to prove its existence other than through its presentation as a translated medium displayed via the light of an output device. If a computer is taken apart, the files are not found inside. Even the base language of binary is not viewable, just a collection of connected hardware devices. Timothy Binkley summed up this key difference in type between analogue and digital respectively; “One is focused on concrete preservation and presentation, the other on abstract storage and manipulation”. (1990)

This makes it difficult to place value on a digital creation, as the format is temporary, intangible, and as a string data, repeatable, with the idea of an original invalid after duplication, as Timothy Binkley noted:

“Digital media have no original. The information is immediately spirited away into electronic circuits and magnetic disks that are inscrutable by the human eye and ear. It moves freely from one digital medium to another, and by the time it is finally “saved” in what is likely to be a tentative version after a session at the machine, it has to be reinscribed and masticated numerous times. There is no authoritative original.” (1990)

A file could contain a literary work, a piece of digital art, a mathematical algorithm, any of which could potentially be ground-breaking, astounding pieces of work, but with the above issues factored in, a contradiction is created, and work becomes invaluable unless a physical version can be generated. A piece of digital artwork can be observed, admired, and owned in principle, however like natural elements such as cliffs and waterfalls, remain invaluable.

With the format itself displaying philosophical sublime characteristics, there possibility of the format to convey feelings of the sublime take on a new possibilities, as both medium and metaphor.

Digital artwork has more in common with abstraction by the nature of its medium. The romantics used nature directly to depict the natural sublime, leaning towards the abstract as a method of expressing feeling, whereas the abstract impressionists used abstraction as an experiential device, effectively stepping into the emotional output of the romantics. By combing projections and animation in an environment, the digital medium can repeat the gesture, by bringing the abstraction into a surrounding, responding form, even if the illusion is not concrete. Although installation artists such as Jams Turrell have already explored this gesture, digital projection can be mapped and transferred onto any surface.

One such artist who does this is Diana Thater. Using multiple surfaces of the available space, her work ascends traditional methods of displaying multimedia.

Peter Luminfeld writes “Thater, to begin with, eschews what video artists routinely embrace: the black room fetish, the desire to transform portions of galleries, museums or found spaces into videoteques, darkened pseudo cinemas for the contemplation of video artwork. Instead, she has long held fast to the dictum that her work should be seen in ambient light, that it should function within the constraints of its space and flow plan and work within a video’s limited colour palate.” (2001: 137)

By using multiple surfaces, images can take tangible forms and distort them using light, changing a surface which we would ordinarily regard as static, and moving the viewer into a state of confusion, at the edge of understanding.

Luminfeld continues “Dealing as it does in scale designed to dwarf the body, architecture is the only art that can strive towards the sublime; Thater’s trick is to turn video into architecture, throwing the image up to play over the found space of her installations.” (2001:141

As mentioned in the previous chapter the concept of large scale canvases to evoke the sublime was mentioned repeatedly by the abstract expressionists, as a means to encompass and act as an environment. The Rothko Chapel (above) can draw parallels with the colour washes of White is the Colour (2002) (below), where the entire room is a washed with a calming blue pulsating projection.

Jennifer Steinkamp is another artist who uses computer based projections to create moving canvases of static architecture, using “dead space” to create projection mapped illusions. Her larger works, such as Swell (1995) (above) encourage user participation, inviting the viewer to become part of the environment through the interplay of projection and shadows, offering the person but to participate by no choice by placing the projectors low and at the back of the available space. Through this immersion and participation the person can feel linked to the large images in front of them, as opposed to a distant observer, operating outside of the work.

Projection and digital arts do however, have an underlying link to the natural sublime through the use of light as the method of display for digital art. Be it via a screen or projector, the most powerful element at work in nature still entices the viewer, linking even the most advanced displays of technology to something fundamentally primitive.

Hyper real computer graphics are at the other end of the scale to abstract imagery, however the inability to truly capture natural environments through exact portrayal due to the lack of other sensory involvement, in the same way the Romantic painters could never evoke the scenes they painted with immaculate detail, instead opting to reveal the feelings behind the painting, means a lack of empathetic response, so there are some issues of conveyance which the medium will not transcend. Oliver Grau comments:

“It is not possible for any art to reproduce reality I its entirety, and we must remain aware that there is no objective appropriation of reality – Plato’s metaphor of the cave shows us that. It is only interpretations that are decisive. This has been one of the major themes in philosophy in the early modern era the work of Descartes, Leibniz and Kant can also be viewed as marvellous attempts to reflect on the consequences that result from perspective, the notions of presentation and thus the cognitive process, which ultimately cannot be overcome”. (2003: 17)

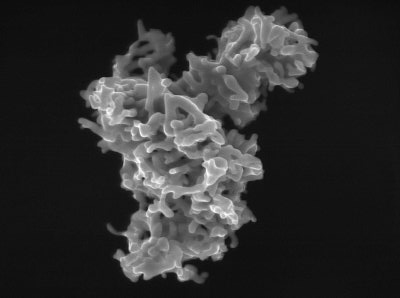

Technological advancement has also allowed for the revealing of the previously invisible. Simon Starling’s Inventar Nr. 8573 (Man Ray) (2006) (above), involves an automated slide projector enlarging a photograph by Man Ray. With each image, the picture moves closer, revealing the ink which makes up the print of the image. Using microscopic technology the silver particles become photos in their own right, complex worlds invisible to the eye. The detailed minutiae become as sublime as a grander narrative due to its endless complexity, which goes on indefinitely. This overwhelming amount of detail contained within a small image is reminiscent of Hugh Honour’s comment on the Romantic painters finding the sublime in a single blade of grass. The enlargement process and endlessly generated detail finds itself at home in digital practice, as mathematical algorithms allow the continuous growth of an image, particularly in the form of fractal art, which follows the same form of endless evolution.

These three mentioned strands of digital art all share in common the ability to amaze and inspire awe by creating imagery which challenges viewers perceptions of reality, by editing and manipulating structures, items and surfaces which are tangible to create realities which relate to our world, but in ways which we cannot understand as real, so the seemingly impossible happens before the person. Lyotard refers to the connection between the artistic avant-garde and the sublime with the term novatio, defined as "the increase of being and the jubilation which result from the invention of new rules of the game, be it pictorial, artistic, or any other." (David, 2011) This breaking from tradition comes with the relatively new format of digital art, which can redefine assumptions about what reality means. Lyotard supports this idea when discussing post modernism, which he believes "cannot exist without a shattering of belief and without discovery of the 'lack of reality' of reality, together with the invention of other realities." (David, 2011)

No comments:

Post a Comment